Years ago, I lead the web development of a new platform for selling life insurance online (which provided white-label abilities).

This was one of my biggest professional accomplishments given the many technical and political constraints. But that’s a whole other topic for another day.

This was before I understood domain-driven design. Since then, I’ve wondered: what this might have looked like using a domain-driven approach?

Here are a few points we’ll cover:

- Event storming: what it is and how to start modelling a business domain

- How thinking of a system or business domain in terms of domain events can really help clarify things

- Some important problems that life insurance businesses might face

- How to tackle interactions with external systems/APIs better

- How certain distributed patterns can improve the UX of a system

Event Storming

Event storming is a workshop that is usually held to discover and learn about how a business works. You invite all relevant stakeholders and use sticky notes to discover what domain events occur, and what impact or additional processes they might lead to.

I’ve also found event storming to be helpful even in smaller settings and within smaller team discussions or design discussions.

For more, see the book by its creator on leanpub.

In this article, I’ll be using a simple version of event storming so we can focus on the important points.

Overview Of Past Design

This system was designed for (a) the main insurance provider and (b) 3rd party insurance providers to allow their customers to apply for life insurance online. It was configurable in that 3rd party providers could choose which parts of the general application process would be included, where the entry point would be, and other customizations.

Generally speaking, the process went like this when dealing with applications on behalf of 3rd party providers:

Accept some HTTP POST data from an initial form filled out by a third-party provider’s customer.

The user continues to fill out the online life insurance application (with multiple steps).

- First, general contact information.

- Next, information about beneficiaries, etc.

- Then, a medical questionnaire.

- Etc.

Once done, the user would provide their banking information.

It would then process the application by calling a remote API (synchronously - while the user waited for the UI to refresh).

Finally, it would display whether the application was accepted or not (with the next steps for the user to take).

Everything was done in one massive code-base. All the web UI and business logic were all together.

Some of the problems with this approach were:

- Lack of code quality

- Difficulty in terms of maintainability

- Lack of business processes documented in how the code was structured

- Long-running synchronous HTTP POSTs could time-out and cause processing errors

- And more…

Exploring Our Domain

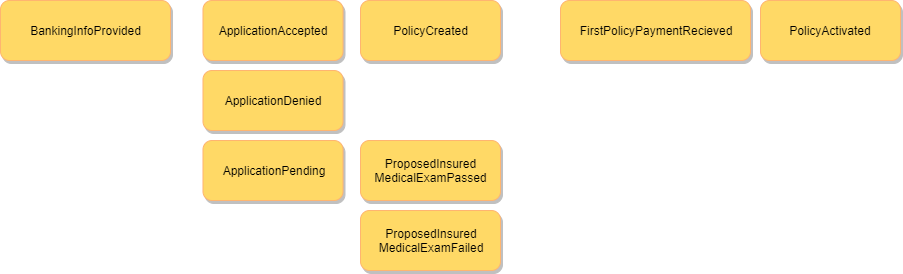

Let’s start to look at the business flow in terms of the events that occur in the domain to give us an overview of what we’re dealing with.

Keep in mind that this is not an exhaustive look at all the domain events, but a very simplified look:

PersonalInformationProvided is considered a domain event because other stuff happens in response.

For example, the insurance company insisted that the system send an e-mail with a token so the proposed insured (i.e. the applicant) could resume their application at a later date.

The results of MedicalQuestionsProvided may lead to the disqualification of the applicant, disqualification of the selected insurance product, enable an entirely different path throughout the rest of the form, etc. These would be domain events too, but they aren’t shown for simplicity’s sake.

The Interesting Parts…

After the application is completed, we get into the next steps:

As you can see, this is where things get interesting.

Right after BankingInfoProvided the system would remotely call the insurance company’s “special” API that would look at past applicant history, banking history, medical history, etc. and make a decision. This decision was returned via the same HTTP POST (🙃).

In some cases, the proposed insured had to undergo a physical medical examination at a later date. Their application was kept in a pending state.

If the application passed, then then the insurance policy would be created (PolicyCreated). Otherwise, a failure just meant there was no policy created and everyone could be on their merry way.

Upon the first payment of the policy (FirstPolicyPaymentReceived), the policy would “activate.” If a policy was not activated within the first 30 days (or some arbitrary duration), it would be immediately cancelled.

Bounded Contexts

In the design of the existing system, there was no concept of bounded contexts. Everything was stored in one massive XML file (yes…the things we have to deal with in outdated industries).

We know that we need to split this up though. How should we?

Pivotal Events

One of the kinds of events to watch out for is what Alberto Brandolini (the creator of event storming) calls “pivotal events.” These are the most important events because they are drivers for major transitions within a domain.

In this scenario, the most important event is PolicyCreated. This is when the application has officially transitioned into a real insurance policy. That’s the end goal of what the user wants in the first place.

Interestingly, this is also where the user-facing web application ended and the backend office policy management began.

Sub-Domains

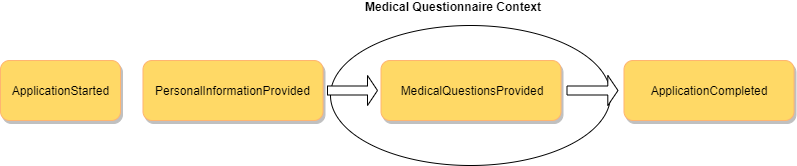

Another interesting area (that you might not be aware of unless you’re familiar with the industry) is that the medical questionnaire is very complex. Depending on how you answer certain questions, many different things could happen.

The code and business logic around this specific area is a hotspot.

Because of the complexity contained within this area, I’d be interested in exploring this area as a sub-domain and treating it as a bounded context.

Sub-domains are not the same as bounded contexts. Sub-domains are still business related divisions, whereas bounded contexts are about what boundaries our software has. Many times, though, they do match - especially at the beginning of modelling, like we are doing. But, if the business structure changes then the sub-domains might change (with the business) while the bounded contexts are still baked into the software.

Definitely, from the business’ perspective, the MedicalQuestionsProvided is a pivotal event. It’s the main driver for whether a proposed insured is eligible for coverage or qualifies for additional “bonus” insurance add-on products.

In the existing system, this part of the system was the hardest to build and maintain!

This is where the main concept of bounded contexts shines - you can draw a bubble around a specific area or problem space that’s complex and keep that complexity isolated. No one else needs to know how it works. It just needs to know what happens at the end of the questionnaire.

Keeping in mind though that we can’t just create bounded contexts wherever we want. In this case, we’ve identified (what seems to be for the moment) a pivotal event.

Language

Also, if we dig deeper with domain experts, we would find that the (ubiquitous) language used in context of the medical questions is very specific to the medical questionnaire.

For example, in this context, when speaking about the applicant, it’s in terms of their health, physical well-being, etc.

This is the only place in the entire domain where this language is used about the applicant.

Transitions Between Sub-Domains

What you’ll notice is that the flow of data is from one context, into another, and then back out into the same one again.

Usually, in typical DDD examples, you see data flow from one context into another and the flow never returns to the original context again.

My gut feeling is that these kinds of complex sub-domains that are smack in the middle of some over-arching business process or other parent domains are common in real-world domains.

Naïve API Calls Vs. Sagas

One of the major issues with the existing system was that it would issue an HTTP POST directly from the web application to the insurance provider’s “special” API that would approve or decline an application.

Again, this easily leads to issues like:

- HTTP timeouts due to network issues

- Errors when the endpoint was down

- The request just took too long and timed-out…

Since this was a white-label product, that API would not necessarily be controlled by the insurance provider who we were building this for. So, we had no control over the performance and availability of that API.

How would I do this today?

To re-cap more clearly, here are the steps needed (barebones):

- Submit the application (via HTTP POST)

- Wait…

- Make sure to retry on errors…

- Abort if the external system never responds

- If it does respond, then give the results to the user

This type of long-running job/process is usually best done using the saga pattern.

Other considerations when dealing with these type of long-running jobs might be the routing slip pattern or the process manager pattern - both of which are similar to the saga pattern.

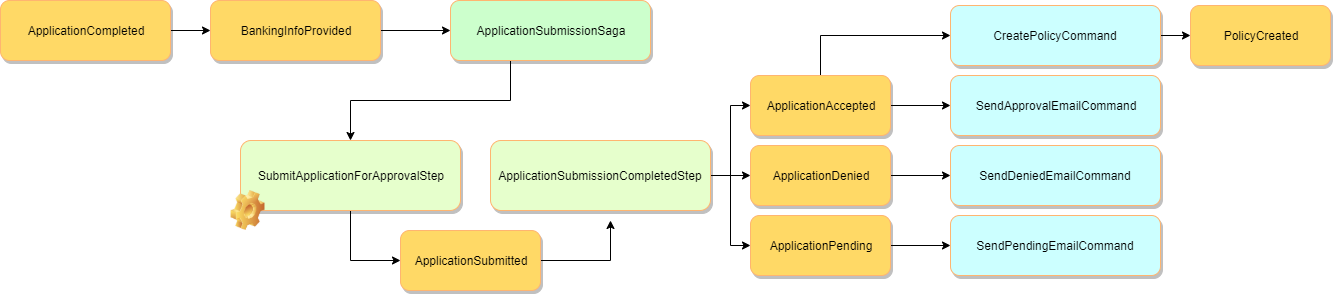

With the saga pattern, here’s roughly what I would envision:

This looks a lot more complicated, but please bear with me for a moment.

Notice that instead of issuing the HTTP POST “plain-and-simple”, the BankingInfoProvided event will kick-off a long-running background job. Specifically, the ApplicationSubmissionSaga.

This saga has two handlers:

- The first will attempt to call the API and submit the application.

- The second will receive an asynchronous event informing it of the submission status and issue further events or logic.

Why? What does this give us?

Resilient Systems

In the original design (direct HTTP POST) - what happens if the external API is not even running?

Oh…

I guess the user is out of luck. They can’t even submit their application…

What if this happens when using the saga pattern?

The saga would fail, then go to sleep and re-try at a later date (since it is a background process). If the external system comes back up the next day then the saga will succeed in submitting the application and continue!

Note: This re-try process is indicated in the diagram above by the orange gear on the SubmitApplicationForApprovalStep.

This way of dealing with a distributed transaction or long-running business process (even if the external API isn’t owned by you) helps you to build systems that can fail and are expected to fail well.

Implications For UX

Let’s compare the two designs in terms of impact on UX. Yes, this difference in modelling impacts UX in a huge way.

With the naïve original design, if the external system is down, the user cannot complete his application. So… the user will have to come back to the website at a later date and “try again!”

What about with the saga?

Here’s where using this pattern shines: the user will “complete” his/her application and we will tell them, “You will receive an e-mail within the next 24 hours once we’ve finished processing your application.”

The user goes home and eventually, at some point in the near future, will get an e-mail telling them everything they need to know.

Note: In the diagram above, you’ll see that I’ve added the commands around this part of the process.

But, what if the external system is down now?

The user doesn’t know. They’re gone. We’ve designed our system such that the user isn’t needed for us to communicate with the external API and deal with failures.

What is the user’s experience?

Awesome.

The implications of this are huge. This is the difference between systems that are easy to use and annoying and difficult to use.

This can affect the branding and reputation of the insurance company.

If users can’t even complete their application because they need to have their web browser open so that our system can communicate with the insurance providers API… that’s crazy. Really bad.

The Importance Of Modelling Your Domain Well

This comes back to the idea of modelling your domain well. This is all modelling. We haven’t written any code, but conceptually we can know what would happen with both designs.

This is why it’s important for companies who want to succeed and give their users the best experience possible to hire developers and engineers who are good at modelling business domains and processes like this.

It literally could be the difference between a company’s success and failure!

And it’s one look at why learning to model with these tools is important as a developer/engineer.

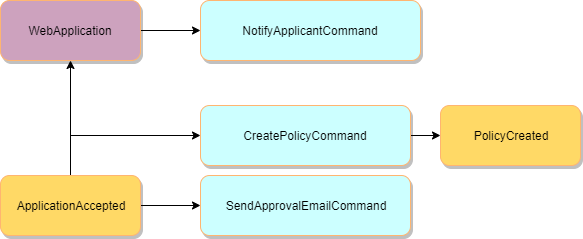

Problem! Business Stakeholders Disagree

Everything is fine and dandy now. Except: they do not like the fact that the user cannot get immediate feedback of the application’s approval status on the web site.

Yes, the applicant will get an e-mail.

But, the stakeholders also want to keep the web site able to display the results to the customer.

What do we do? Say no?

Our new design means that the results of the application approval/denial is a background process now - it’s disconnected from our web application.

Here’s one solution you might have thought about: the web application can also subscribe to the ApplicationAccepted, ApplicationDenied and ApplicationPending events and use web-sockets (using SignalR, etc.) to “push” the results back to the user’s browser.

This might even include showing a browser notification (even though we all hate them)?

Either way, it’s one way to satisfy all the requirements we have so far:

Conclusion

This was a somewhat primitive look at this domain. There’s so much more to it.

Hopefully you did learn something about modelling business processes though. Sometimes, just by changing how we process one step in a business flow we can make a huge impact!

If enough people enjoy this and provide feedback then I might just dig into some more specific problems and do some more intense modelling 😉.

New Site!

I’ll be writing new content over at my new site/blog. Check it out!